Heatwave During Wildfire: Indoor Air Quality Decisions

My husband and I looked at each other in the pre-dawn darkness on September 5, 2020. The thing we were worried about was happening. Weather forecast showed heatwave for the next few days in midst of heavy air pollution from wildfire smoke. This meant the two strategies we’ve used to manage thermal comfort and indoor air quality were at odds. We asked ourselves how do we manage this? Which do we prioritize?

Here’s the background to frame the situation we faced.

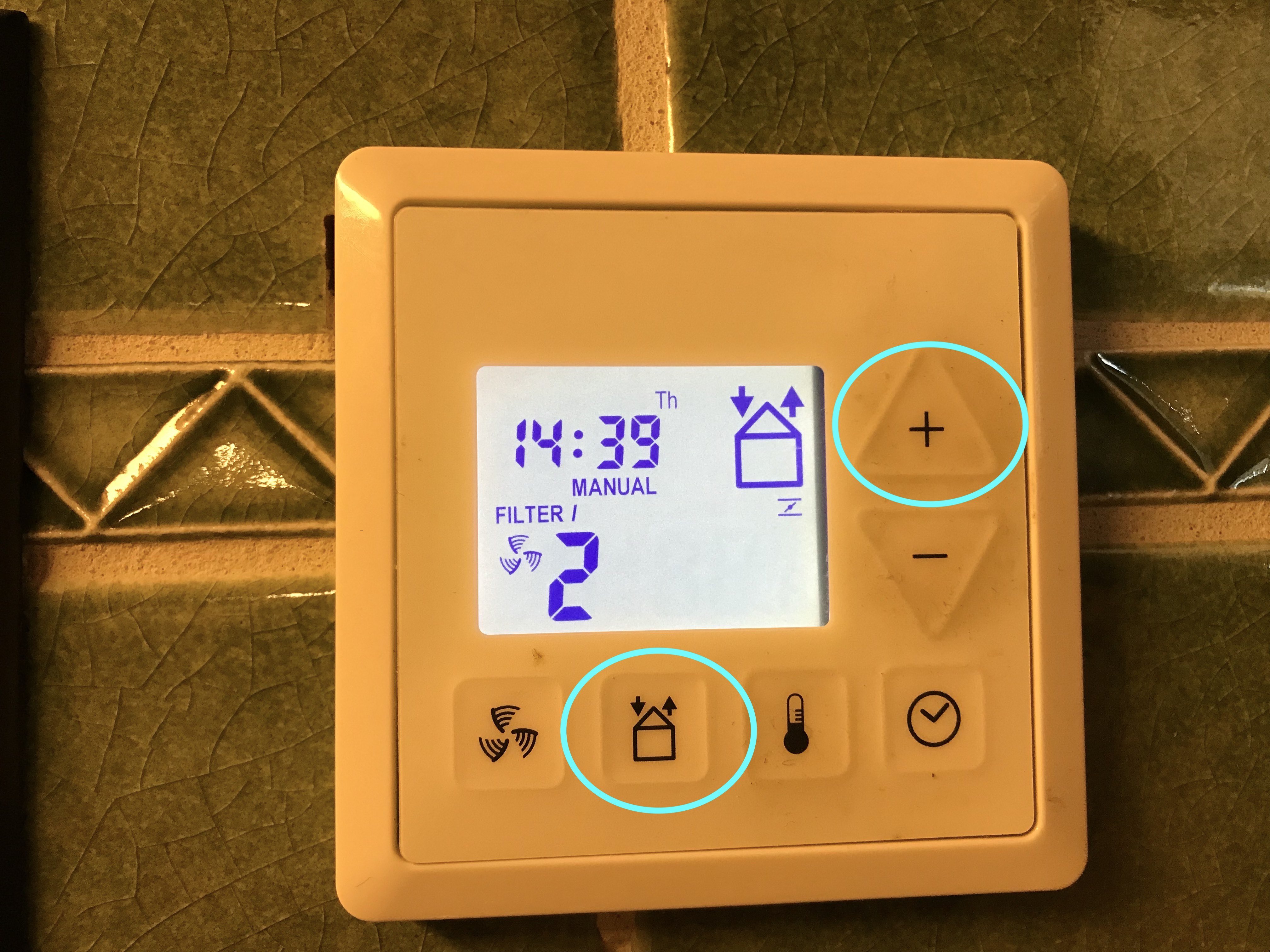

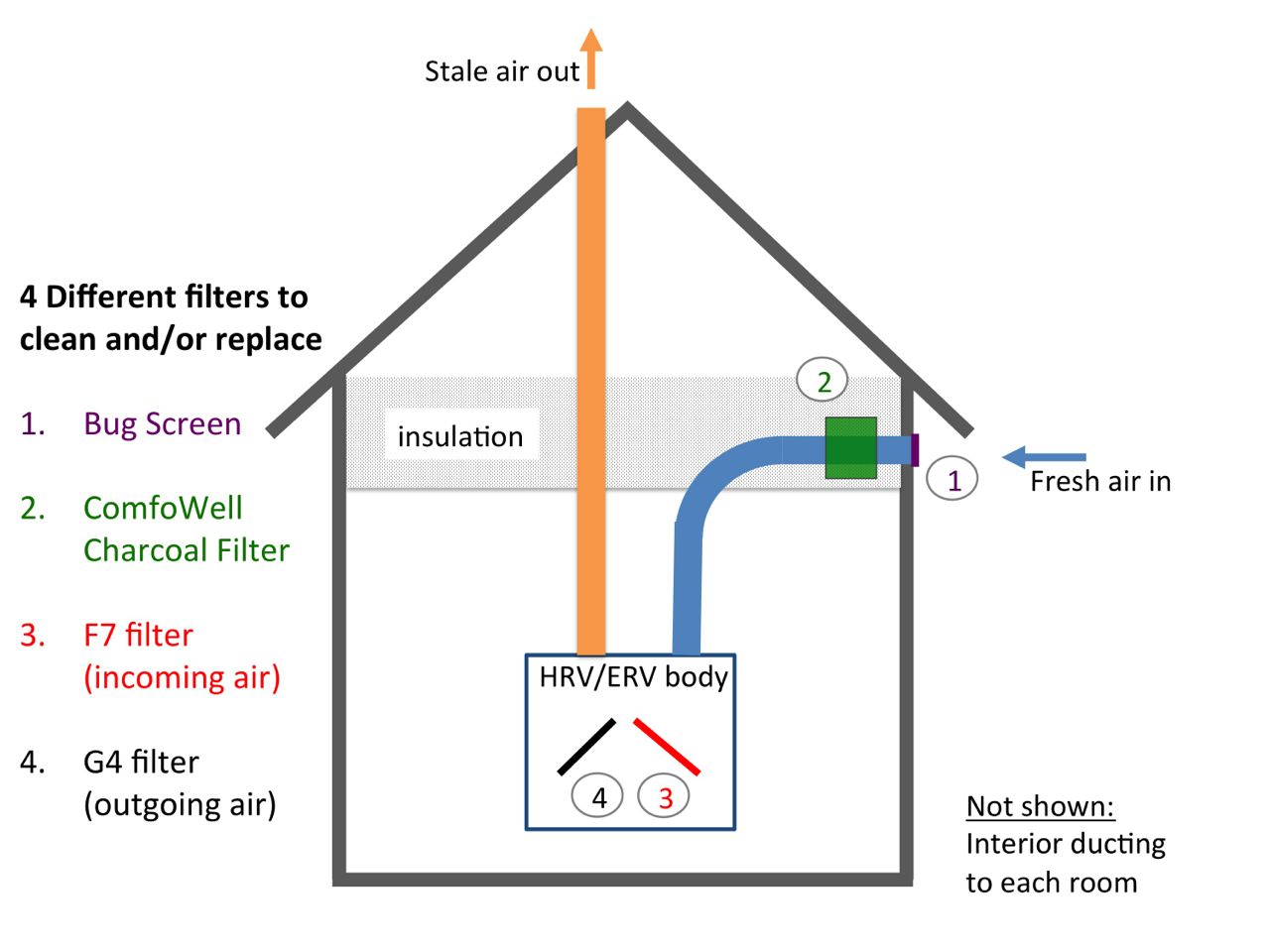

We don’t have an air conditioner to cool the house. The mild climate we have in the central coast of California allows us to hum along in comfort with the heat recovery ventilator (HRV) in our Passivhaus. When we do have a heatwave where the daytime temperature soars to about 100F (38C), we pre-cool the house during the early morning hours by blowing a box fan in the hallway after opening all of the doors and windows. Some call this strategy “night flushing,” and it works for us because our coastal climate lowers the overnight outdoor temperature to about 63F (17C).

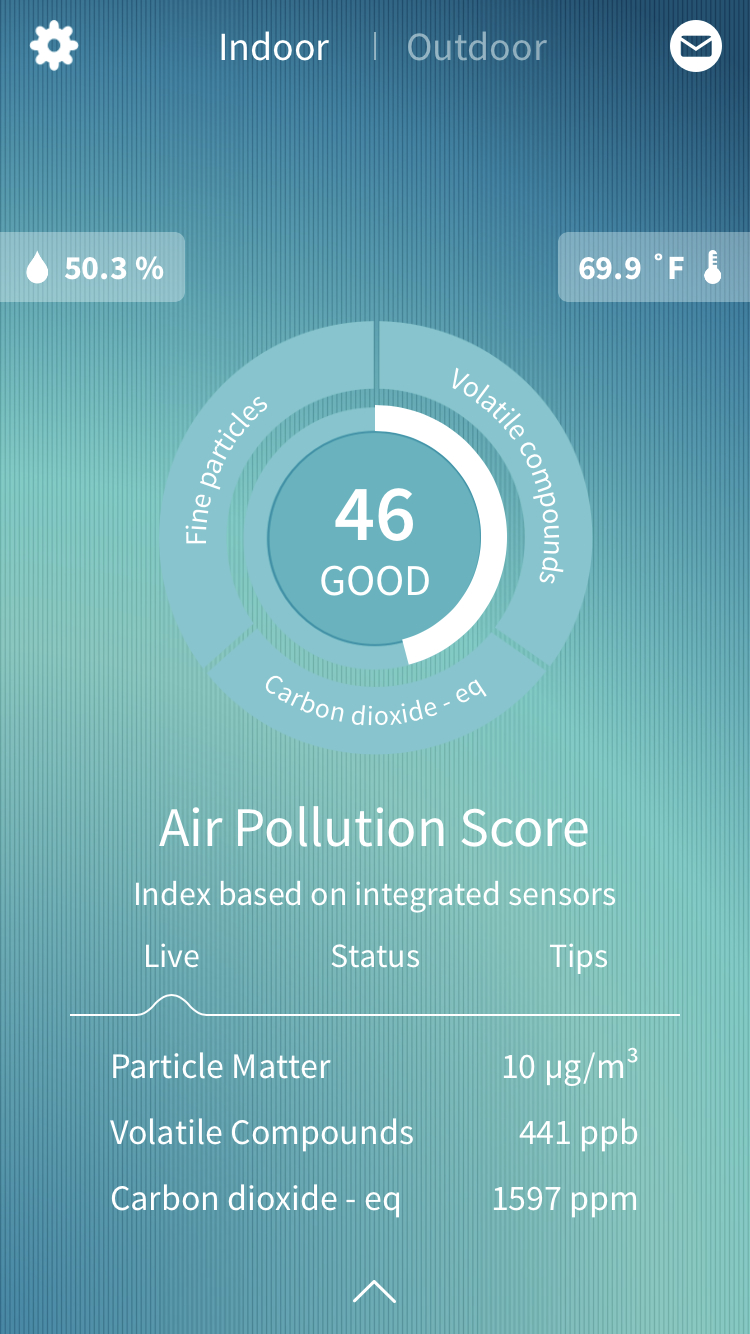

Our air pollution routine is the opposite of the night flushing routine. When the outdoor air is bad, we turned off the HRV and wait it out. This works for a temporary event in the winter when neighbors light up their fireplaces. We turned the HRV back on after a few hours. This had been effective in the winter.

It’s early September when we faced this decision, but first let’s rewind to the beautiful lightning show of August 16. I saw several friends post beautiful photos of the lightning storm like this one.

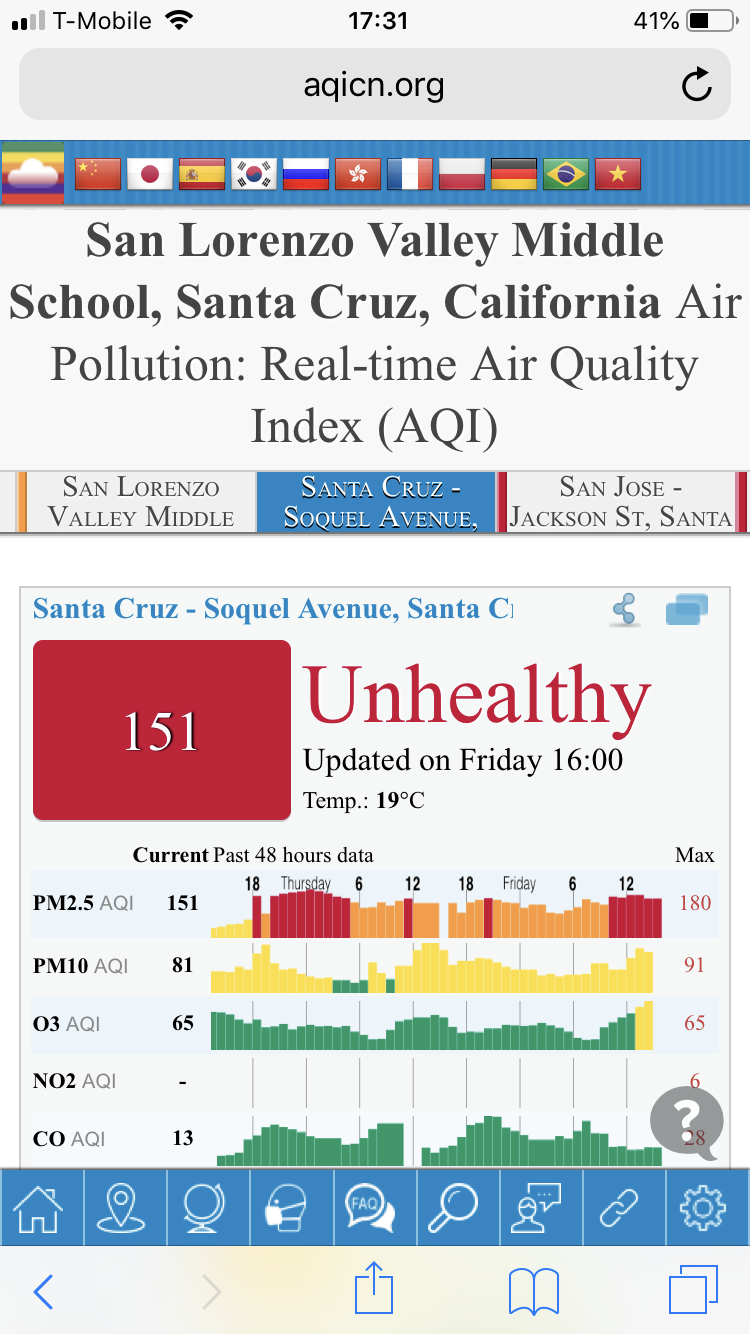

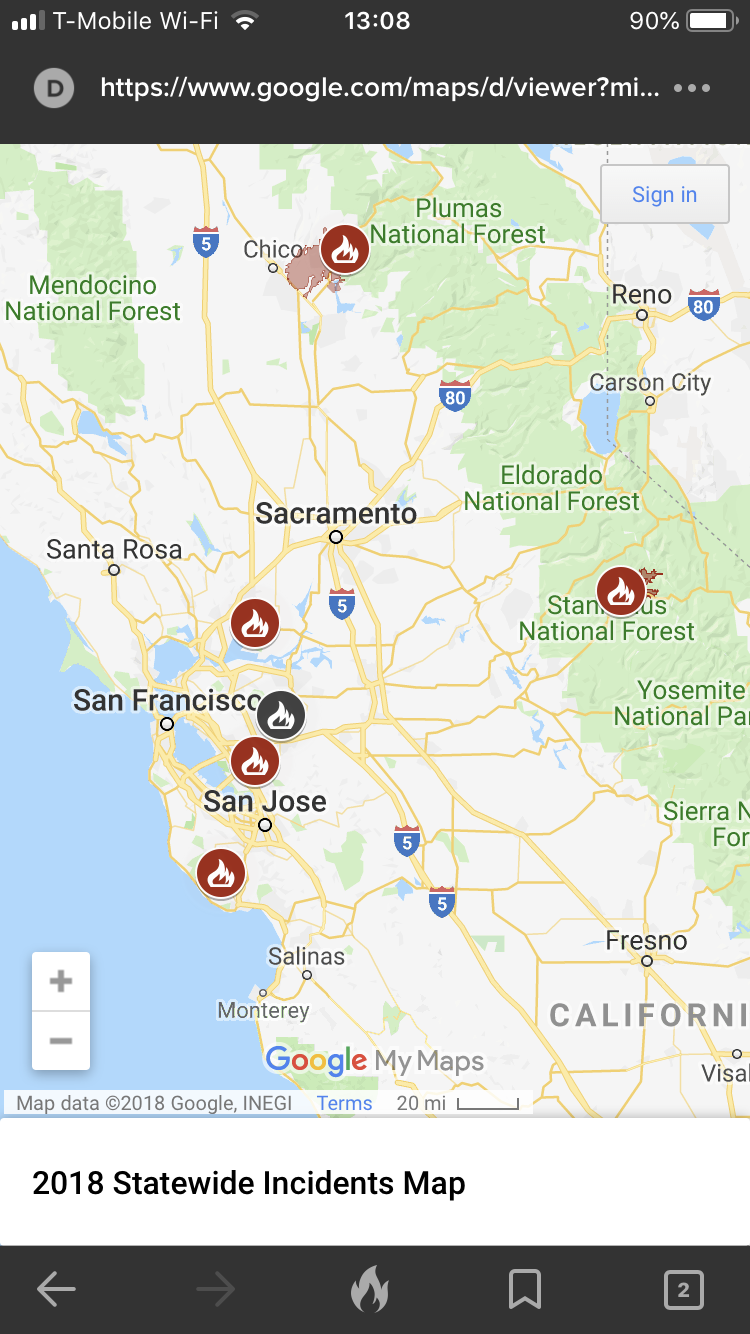

Over 11,000 lightning struck that night and started several wildfires. The closest one to me was the CZU Lightning Complex Fire that started on August 16, 2020 and eventually burnt 86,509 acres (35,009 hectares) and destroyed 1,490 buildings. At one point, the fire was less than 10 miles away from my house and we had considered a voluntary evacuation. Smoke filled the air. Ashes covered my car. As flecks of ash clung to our clothing and hair, I appreciated the mask I was wearing for COVID-19. The air quality during the first few weeks of the fire varied, depending on the direction of the wind. Early on when the wind was blowing from the ocean, the outdoor air was good. When the wind shifted, we got not only the ashes from the CZU fire, but several other wildfires burning in the 200-mile radius.

20 days after the CZU Lightning Complex Fire started, the heatwave came. On the morning of September 5, 2020, we prioritized thermal comfort over indoor air quality. Why? Because we could deal with the dirty air inside the house by running air purifiers inside the house, but we don’t have another way to cool the house. Purple Air map showed the air quality in our neighborhood to be moderate (Air Quality Indicator range 80-90), so we went ahead with the night flushing.

NIght Flush: windows open

Night Flush: box fan circulating air

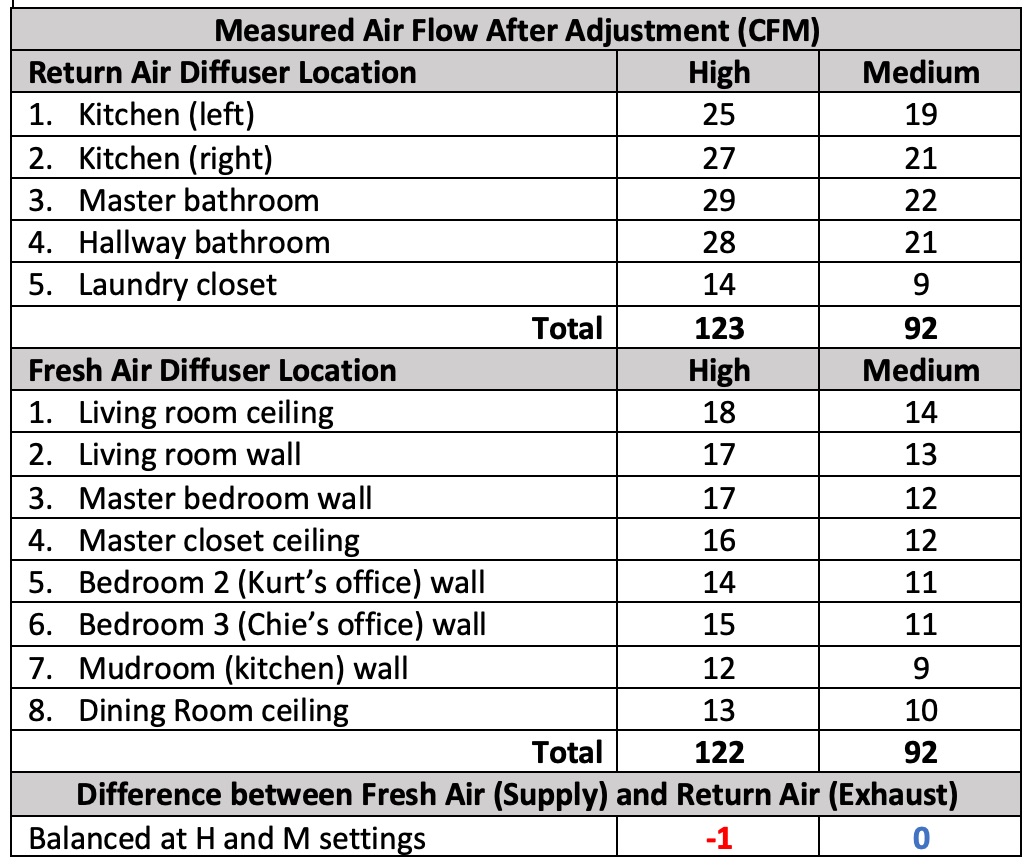

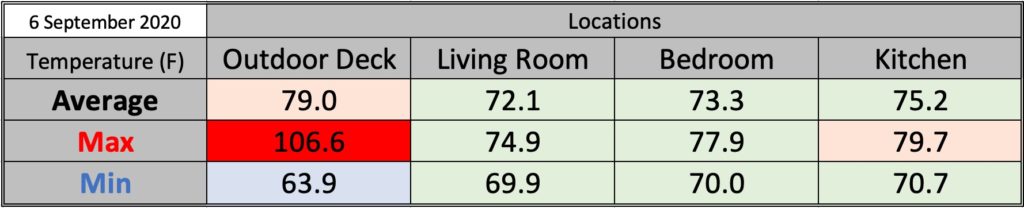

Night flushing was effective. It allowed us to maintain comfortable air temperature inside the house. Here’s the temperature snapshot on the second day of the heatwave.

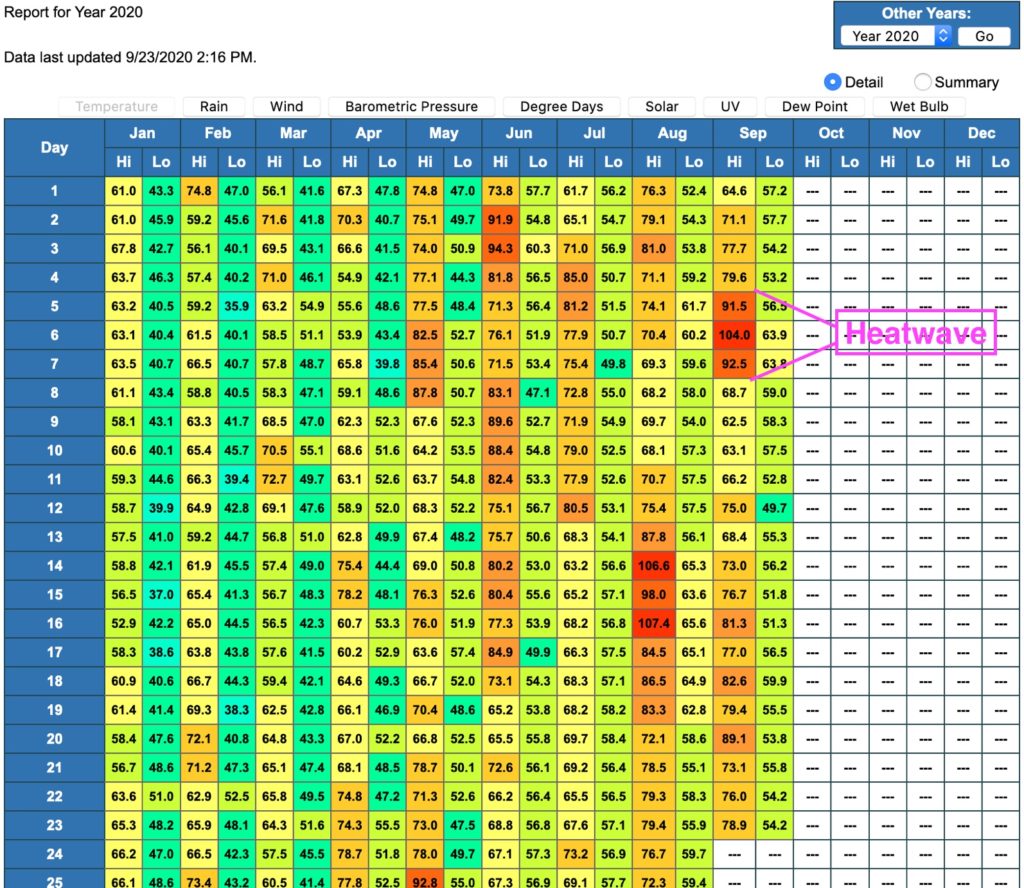

We repeated this night flush routine during the heatwave. See temperature chart below. This is from my favorite local weather station weathercat.net.

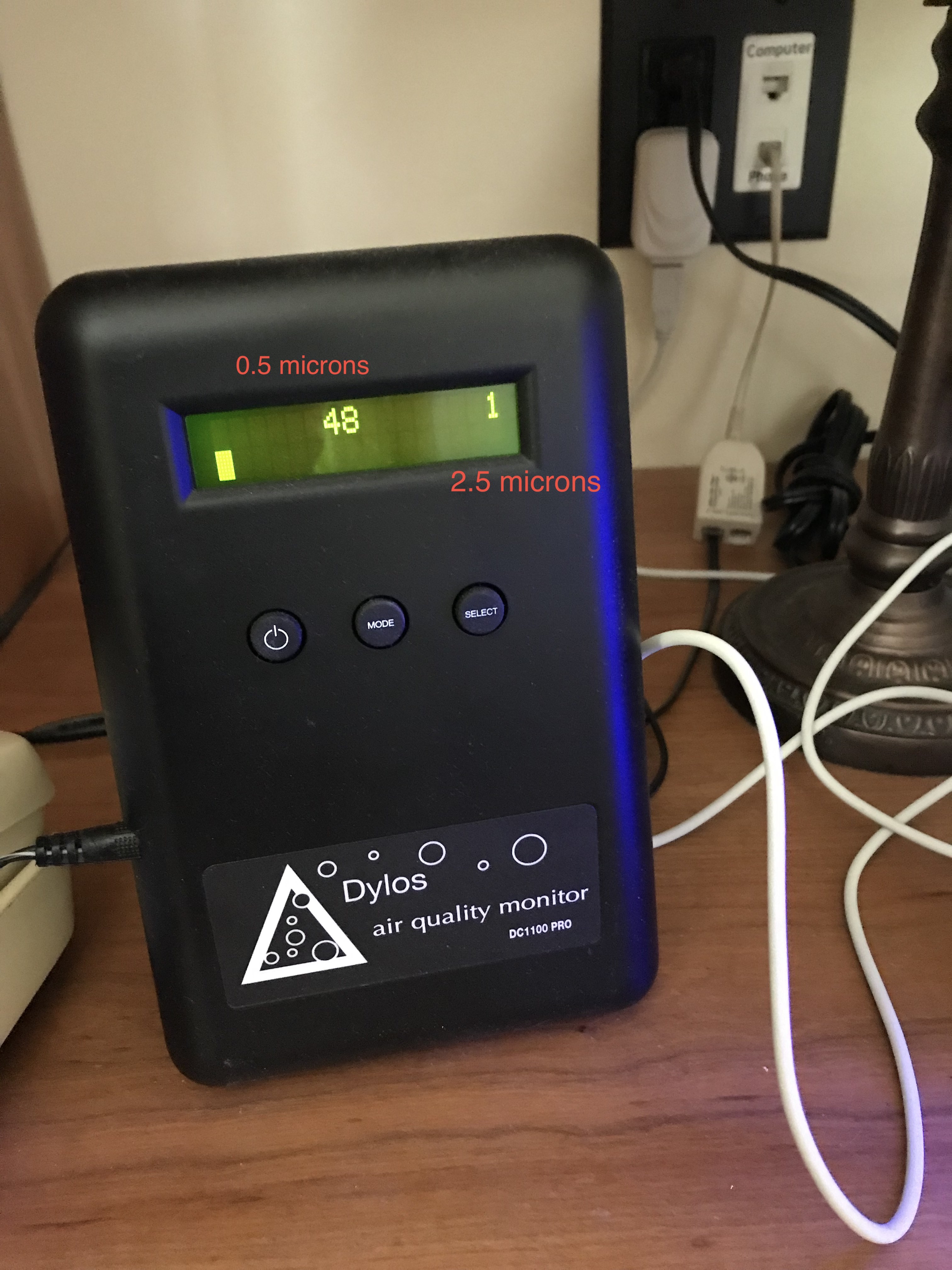

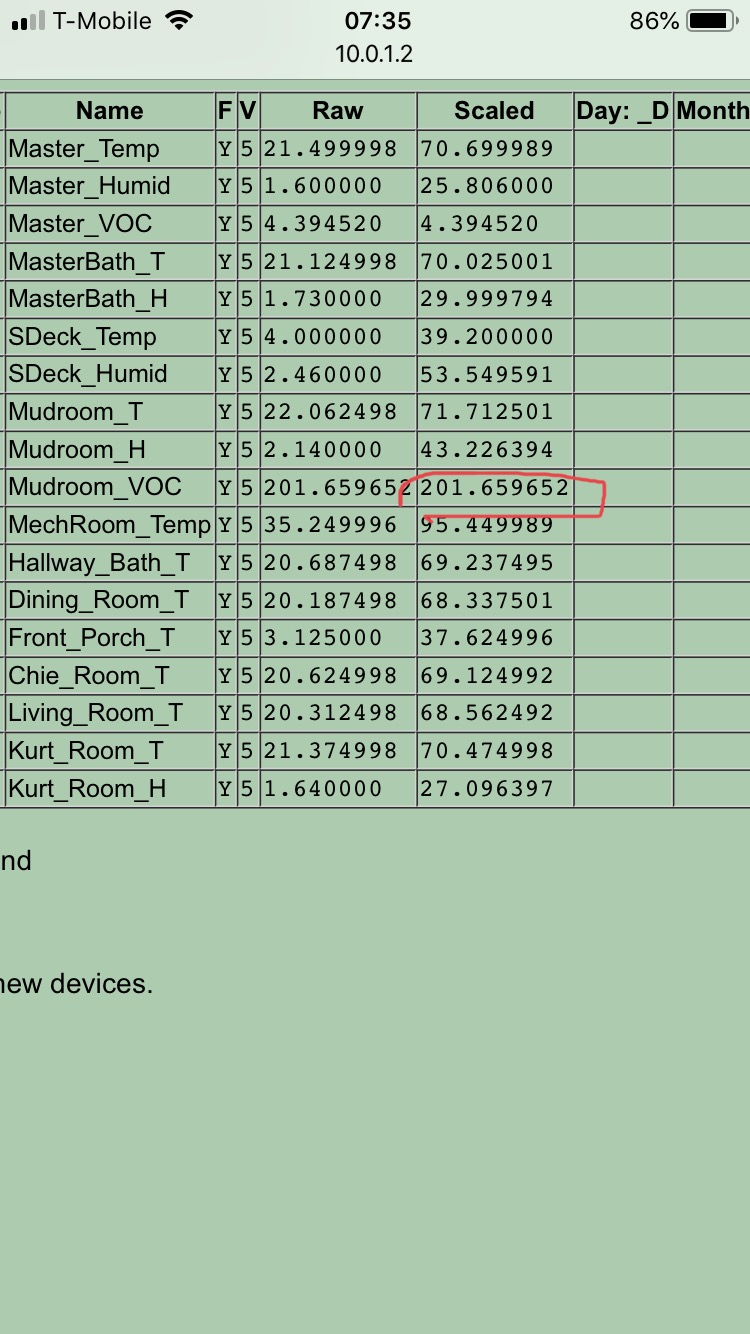

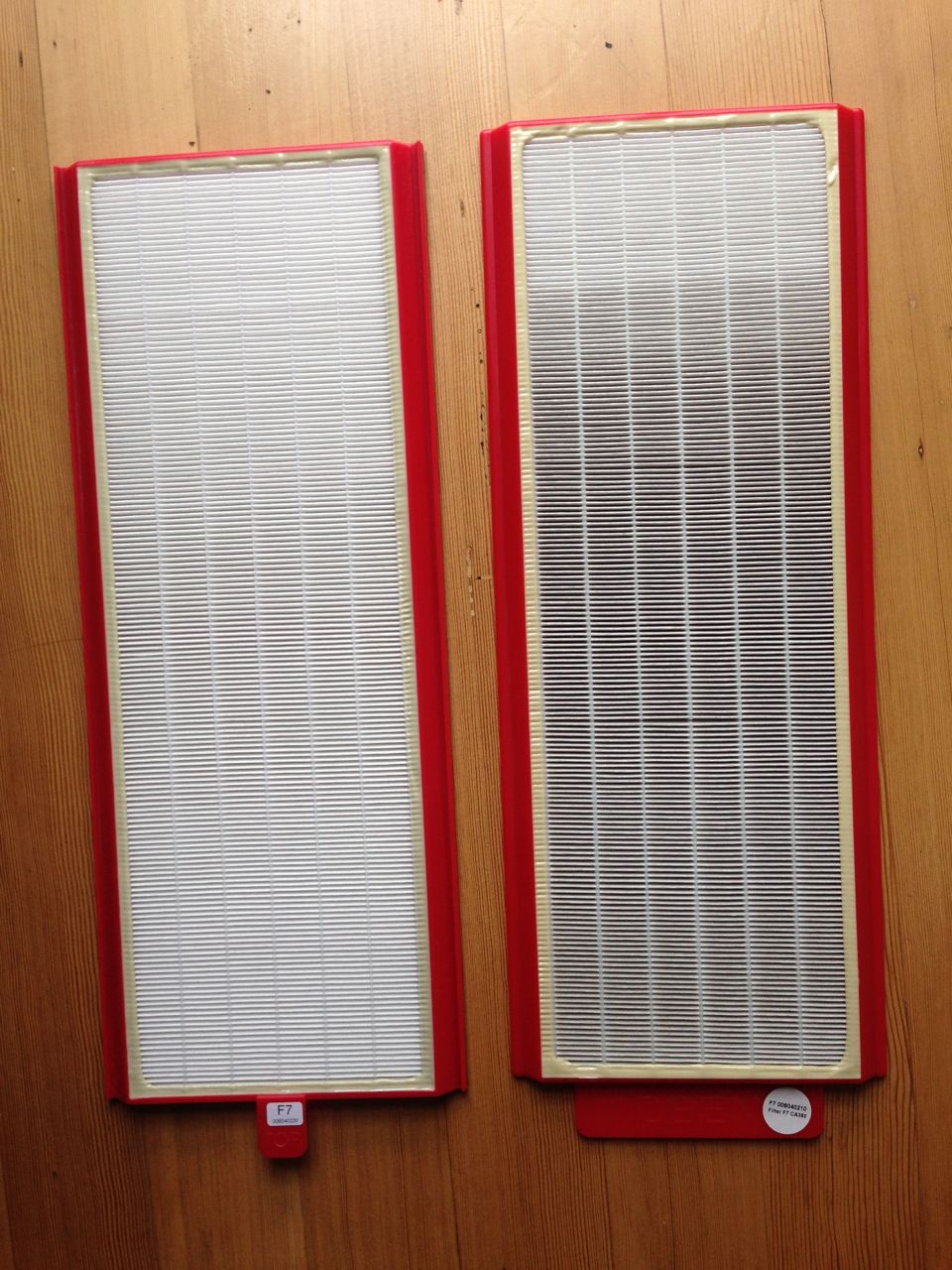

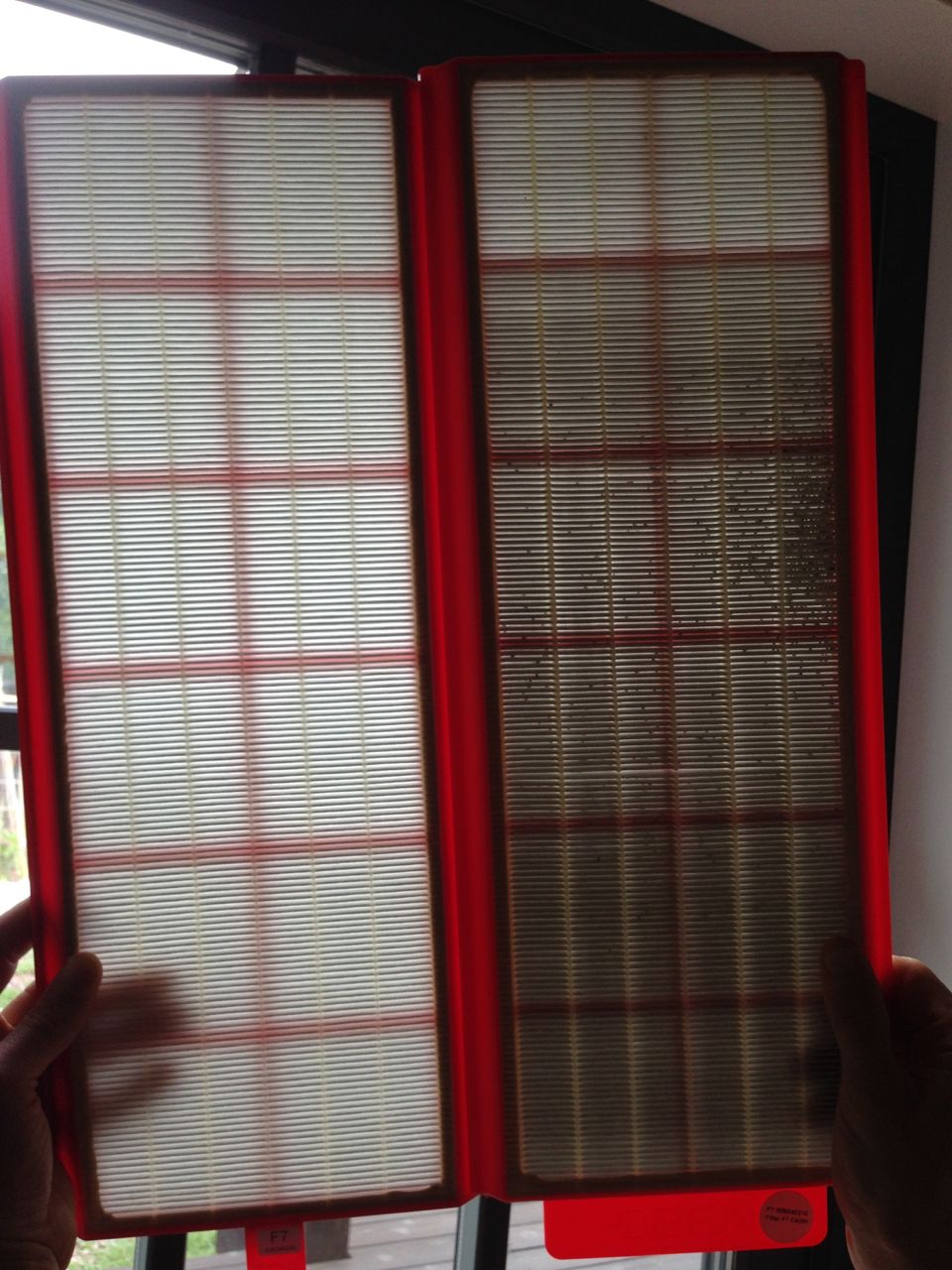

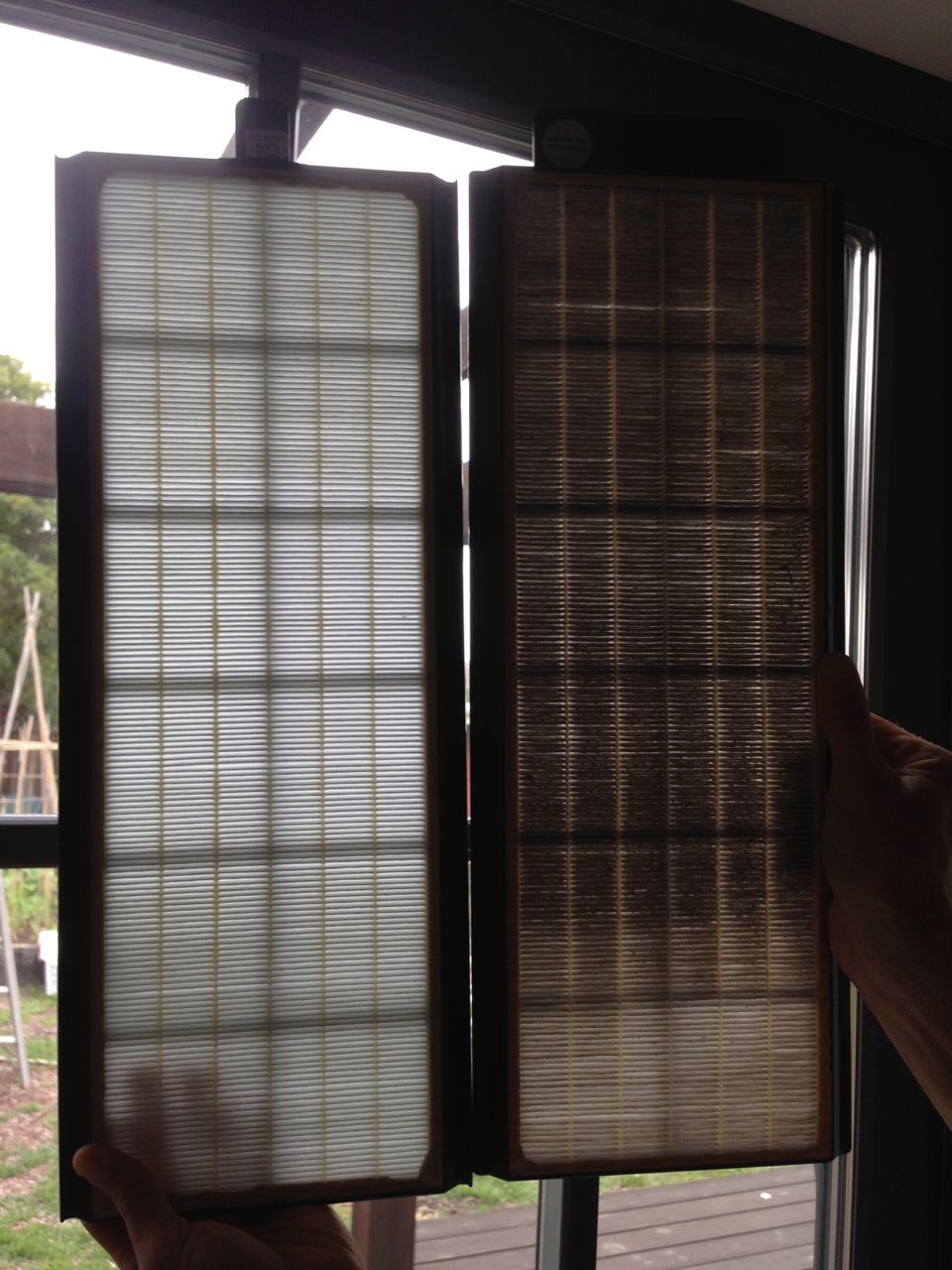

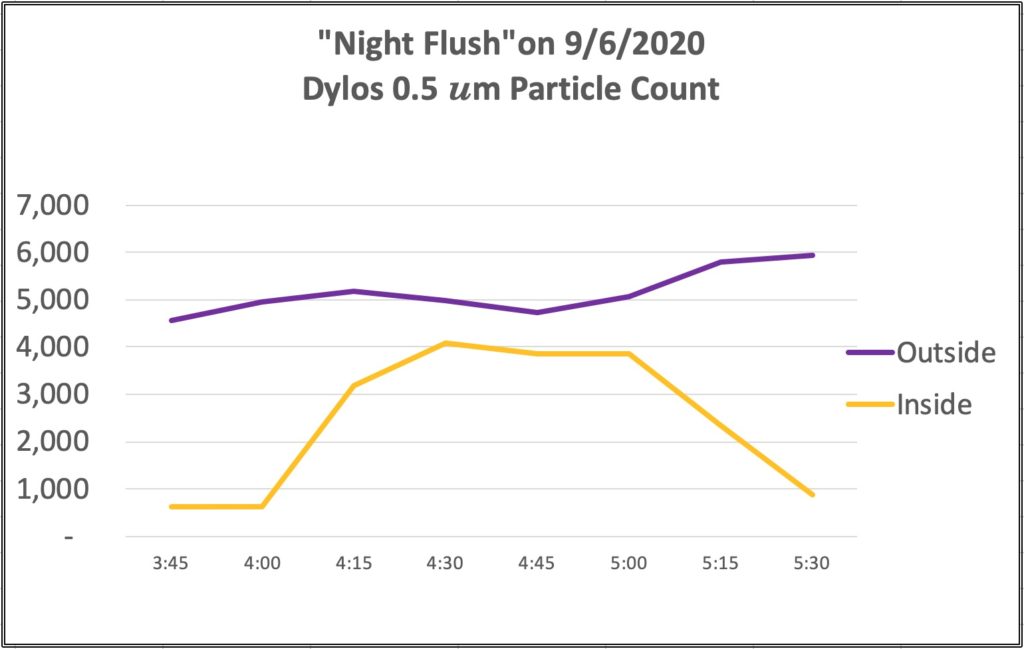

We used Dylos DC1700 to measure the air quality outside and inside the house. Here’s a graph showing the particle count rising when we did the night flush. Indoor particle count dropped with the air purifiers running on high after the windows and doors were closed.

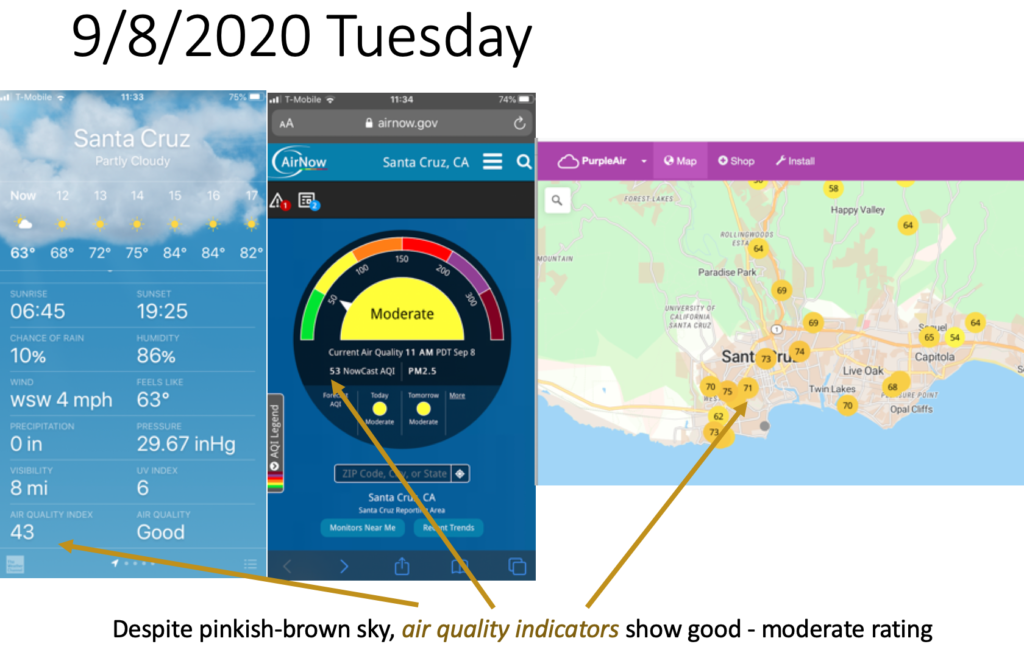

On September 8, 2020, something strange happened. The heatwave that was forecasted abruptly ended. The sky got dark. Brownish-orange sky all day. There was so much pollution in the air that the sun could not get through and we were spared from the heatwave. Eerie images filled social media.

The depressingly dark sky felt foreboding, but the air quality at the surface level didn’t get much worse.

I suspect the smoke particles floating about at higher elevation took a few days to fall to the ground because that’s when the particle count shot way up. How much did it increase? That will be in the next post.